Crimson Tide honors Hudson with number retirement

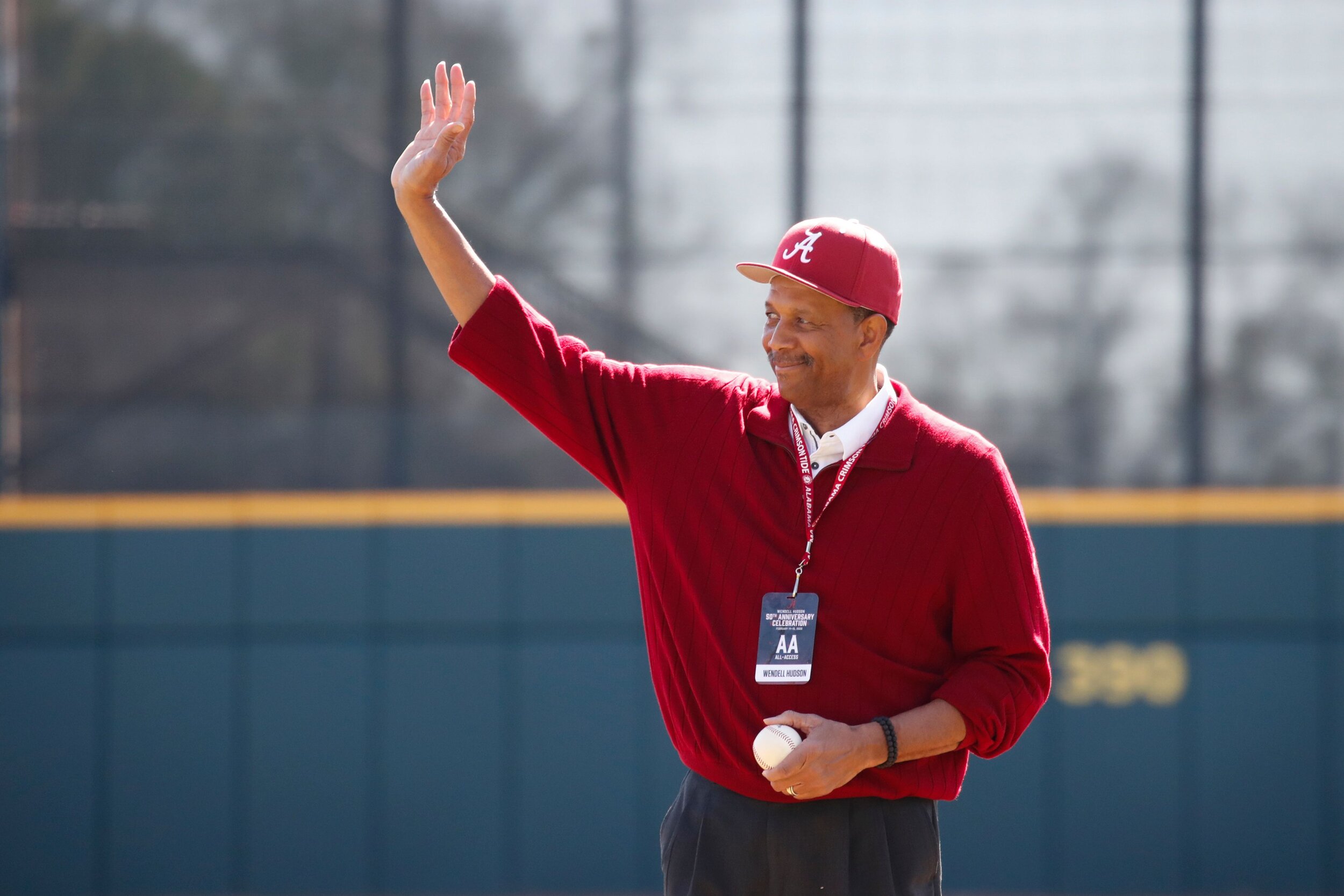

The University of Alabama honored former basketball great Wendell Hudson on Saturday by retiring his number. He also through out the first pitch at Alabama’s baseball game with Northeastern (Photos - UA Media Relations)

By TIM GAYLE

TUSCALOOSA - Fifty years after becoming the first, Wendell Hudson relived that distinction on Saturday.

The first African-American to ever receive a scholarship from the University of Alabama became the first in Crimson Tide history to ever have his number retired during a halftime ceremony at the Alabama-LSU men’s basketball game at Coleman Coliseum.

And Hudson, always the humble guy with the outgoing personality that made him a great athlete and an even better person, summed up his lifetime of accolades succinctly.

“Part of it is that I was a good player, which I think I was – you’ve got to think that if you’re going to play – but the other part about it is I don’t think I was a bad person, either,” Hudson said. “I think I kind of carried myself and represented the University of Alabama when I was here as a player, and later on as a coach. There’s nothing out there that is going to pop up tomorrow and they’re going to say, well, we shouldn’t have put that up.”

Hudson, now 68, received a thunderous ovation from the crowd of 12,479 who came to watch the Tide turn back 25th-ranked LSU 88-82 and caught a piece of history in the process.

“My story is not necessarily the typical story of integrating an athletic department and being the first black athlete,” Hudson said, “because I had fun. It was enjoyable, it was a good story. And a lot of times, people don’t want to print a good story.”

Hudson had been a part of the first integrated Alabama High School Athletic Association finals months earlier when his 33-1 Parker High team won the 4A state championship. He recalled his recruitment from then-Alabama coach C.M. Newton and a conversation he later had with Newton.

“A couple of the schools that he went to in Birmingham that were predominantly black, they wanted their kids to go a black college,” Hudson said. “He said Parker was never that way, he never got that feel, so I never got any kind of feel from my high school coaches about coming to Alabama just because of where it was and what it was. It was like, hey, you want a chance to play? Everybody wants to play at the highest level they can play. I looked out there and I thought I could play here.”

He arrived in 1969 and, along with Newton, helped transform the face of college basketball in the South. He was the Southeastern Conference Player of the Year in 1972 after leading the league in rebounding and again in 1973 after leading the league in scoring, earning All-American honors in the process.

He was a trailblazer in those early days of integration, but Hudson never really thought that way.

“We’re talking about 50 years ago,” Hudson said. “You’re talking about traveling on the road here in the South and going to different places to play and some of the people in the stands. I don’t remember a lot of the negative things people said because I was out there playing. The second thing is, if you’re playing and concentrating on trying to do that, you ain’t got time to worry about what the fans are saying anyway.”

He got into coaching at Alabama as an assistant, moving on to North Alabama, Rice, Ole Miss and Baylor before taking a job as the athletic director at McLennan Community College in Texas, where he served as head coach of both the men’s and women’s basketball teams at times during that 17-year stretch.

Honored by the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame and as an SEC Legend, he returned to Alabama to serve as the associate athletic director for alumni relations, appointed by Mal Moore to the position that Moore once held before becoming the athletic director.

In 2008, he talked Moore into letting him coach the women’s basketball team at Alabama and while the Tide never enjoyed any success under Hudson (his team’s went 69-73 over five years), he was at the forefront of a push to get Foster Auditorium restored.

He stepped down from coaching in 2013 and went back briefly into administration at Alabama before retiring and moving to Waco, where athletic director Greg Byrne found him to inform him of the school’s decision.

“When he told me about retiring the jersey, I paused,” Hudson said. “Because I had to take that in. I know the history of Alabama, I know the history of the athletes and all the things that have happened here. And I know the people that have argued about ‘why don’t you retire somebody’s jersey’ here before. For mine to be the first one, it was an unbelievable feeling when I found out about it.”

Saturday was a whirlwind for Hudson, who was honored before the Tide’s baseball game and again during the basketball game. In between, he caught up with former teammates from both Parker and Alabama.

“We’ve got a guy who came back here, he hadn’t been back here in 50 years,” Hudson said. “To be able to see him, embrace each other and be a part of it, a lot of those guys (back for the ceremony) had a lot to do with getting me the ball.”

He was asked to speak to the men’s basketball team as well, but Hudson talked more about potential than his place in Crimson Tide’s folklore, delivering a simple message to the players.

“Every day I tried to be the best player on the court,” he said. “It didn’t matter if it was practice or a game. And I know some of them were looking at me, thinking every day? In practice, too? Everyone in the world we live in today (thinks) I’m a gamer, I’m going to turn it on. Well, if you do it every day, you don’t have to worry about turning it any other way.”

The color barrier that Hudson broke in 1969-70 not only redefined college athletics, it led the way in changing society as well.

“I think athletics have come a long way,” he said. “Even as integration started early, the point guard had to be a certain color because that was the quarterback. But you don’t see that today in college athletics. It’s whether or not you can win because there’s too much money involved. It eliminates all that stuff because you’ve got to win. You’ve got to win or somebody else is going to have that job and if you didn’t win because you were worried about the color of that player that’s out there playing, then you’re done. And everybody has come a long way because people cheer for teams and when you look out there, who are you cheering for now?”